‘SQ117 owes me a glass of fresh milk’: The Singapore Airlines hijacking, 30 years on

SQ117 sits on the tarmac after the hijacking rescue operation.

SINGAPORE: Past 9pm on Mar 26, 1991 – 30 years ago to the day – three men were in various stages of winding down their evening.

Maybank manager Ong Cheng Sng had just settled into his aisle seat on Singapore Airlines flight 117 from Kuala Lumpur to Singapore. Mr Ong, who was 44 at the time, had had a long day and had barely made it for his flight, but he was now looking forward to a glass of milk from the galley and finally getting home.

Singapore Airlines junior steward Ted Ang, 23, was preparing the cabin for take-off. He too had had an exhausting day, having worked on a flight from Singapore to Penang and back, and was now on the return leg of a Singapore-Kuala Lumpur shuttle.

Most relaxed was the Permanent Secretary for Defence Lim Siong Guan. Mr Lim, 44, was reading a book at home in his study upstairs. He would soon be calling it a night.

What would happen next to the three men would forever be etched in Singapore’s history. Two of the men would end their day hoping to stay alive, while the other had to try to ensure that they would.

READ: As a Special Forces soldier, he stormed a hijacked Singapore Airlines plane. Now he's a monk

Various accounts have been written on the 1991 hijack of SQ117, when four Pakistanis seized control of the Airbus A310 in mid-air and effectively took 114 passengers and 11 crew members hostage.

The unmasked hijackers were armed with knives, large cylindrical sticks thought at the time of the hijacking to be explosives, and cigarette lighters.

Three decades after the incident, CNA spoke to the three men and sourced details from other accounts. This is their story:

Tuesday, 9.30pm: Pre-flight

Mr Ong found his economy seat at 38C, which was in the middle of the plane. He had started the day in Singapore but spent most of it in Kuala Lumpur, after a meeting with bank colleagues was shifted there from Brunei at the last minute. Mr Ong was eager to get home as he had work the next day.

“I thought everything was normal,” he said, adding that he occupied the middle row with the three seats beside him empty. “And in a very short while, I'll be home resting together with my family members.”

But the push-back was delayed a little, as Mr Ang remembered four passengers being held up at the gate holding area. They ended up being the last to board. The plane finally taxied to the runway and took off.

Tuesday, 9.50pm: The hijack

As the plane started to cruise, the four passengers who were late to board got up and walked to the toilet. They seemed to enter the cubicles in pairs, Mr Ang noticed. That was weird, he thought before brushing it off, assuming that they were drunk or culturally different.

Mr Ong asked a stewardess for a glass of milk and grabbed a newspaper. An article about the national footballer Fandi Ahmad caught his eye. Then he heard shouts in a language he did not understand.

That year’s Oscars had just concluded, so he thought some passengers were celebrating their stars’ achievements. “But this was not to be,” he said.

Mr Ong recalled one of the shouting passengers, who would later be recognised as the leader of the hijackers, switching to English. “Sit down and don’t move,” the burly man shouted, holding aloft what looked like explosives. “This is a hijack.”

“I was frightened of course,” Mr Ong added. “And I was wondering whether I was in a movie, or whether it was a dream or if it was real.”

Mr Ang stayed calm and approached the hijackers. “My first reaction was, with an SQ smile, I said, ‘Sir, would you like to go back to your seat?’” Another hijacker, even bigger than the leader, punched and kicked him.

Mr Ang was so shocked by the assault that he still remembers what his attacker was wearing – a T-shirt with a picture of Tommy Page, the American singer famous in the 90s.

Mr Ang quickly realised that this hijack was real.

Mr Ong said the passengers reacted with “big surprise”. The stewardesses handing out snacks froze. Everybody sat quietly and nobody moved, Mr Ong recalled. “Nobody expected a smooth flight back to end up in that manner,” he said. “All we could do was to listen to the command to keep quiet.”

The leader entered the cockpit and demanded that the pilot, Captain Stanley Lim, land the plane in Sydney instead of Singapore, or he would blow up the plane. Captain Lim said the plane did not have enough fuel, and that it would crash if he tried to fly to Sydney. The leader then permitted him to land in Singapore to refuel, before continuing the journey to Australia.

Back in the cabin, Mr Ang remembered the hijackers being well-organised. First- and business-class passengers were rounded up and told to sit in economy. Two hijackers were stationed there to manage the passengers, while the leader negotiated with the pilot.

Mr Ang and three male cabin crew colleagues were herded to the galley at the rear of the plane. The remaining hijacker, whom Mr Ang remembered as a young man not older than 30, was sent to keep watch over them.

Tuesday, 10.20pm: The executive group

Mr Lim was about to go to bed when he heard the phone ring. He went downstairs to take the call. It was the police.

An executive group made up of senior officials from different ministries, including the Ministry of Home Affairs and Ministry of Defence, was being convened to manage the incident, as per standard protocol. Mr Lim told his wife he was going to work.

Mr Lim also called Prime Minister Goh Chok Tong to inform him of the incident, and remembered Mr Goh simply saying thank you for informing him.

While the executive group was in charge of making the important decisions in the rescue operation, it had gone through many exercises to prepare for such scenarios. Mr Lim said he felt “really calm”.

“I mean, this is a well-practised routine; we all knew what we had to do,” he said. “And so we just went to Changi and got on with it.”

The command centre at Changi Airport was already buzzing, Mr Lim said. The police negotiating team was in contact with the hijackers. Developments were scribbled on whiteboards.

Mr Lim was briefed on the hijackers’ demands, which included getting to speak to former Pakistani Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto and the release of a number of people jailed in Pakistan.

At 10.24pm, SQ117 landed on Changi Airport’s Runway 1. The hijacker leader ordered the pilot to stop the plane on the runway. It was soon surrounded by police officers, including crack troopers from the Police Tactical Team.

With Permanent Secretary for Home Affairs Tan Chin Tiong overseas, Mr Lim, as deputy chairman, assumed command of the executive group.

“The most important thing we were all clear about, was to secure as best as we could, the safety of the passengers and the crew,” he said.

Tuesday, 11pm: Violence on the plane

Before the plane landed, the steward Mr Ang remembered the hijackers calling passengers brothers and sisters and reassuring them that they would not get hurt. Cabin crew back then were not trained to handle hijack scenarios, Mr Ang said, and so everything he knew about them was from the movies.

“I thought that in a normal hijack scenario, the crew are unlikely to get hurt,” he said. “Unfortunately, it didn't turn out that way.”

After the plane landed, the hijackers kicked and beat the stewards up, Mr Ang said. One of them, Bernard Tan, was forced to drink water laced with an unknown white powder. “I didn't know what that was, but sure enough after about 10 minutes, Bernard was a little bit unconscious and couldn’t stand up,” Mr Ang said.

In the cabin, the passengers had a relatively easier time. Stewardesses were allowed to hand out drinks and blankets, and passengers were given permission to go to the toilet. But in seat 38C, passenger Mr Ong remembered feeling a little annoyed. Despite the many empty seats, a woman had chosen to sit next to him and could not stop asking him questions.

“I just wanted her to shut up because I didn't want to attract the attention of the hijackers,” he said, fearing what they could do. “She was in her 40s and was very upset that I refused to talk to her.”

Things took a turn when hijackers dragged Mr Tan, the steward who could barely stand, to the front of the plane. Mr Ang heard a door being opened and shut. The hijacker leader went to the back and told them: “I’m sorry. I killed one of your friends.”

It later emerged that Mr Tan, at about 11.20pm, was thrown out of the plane, falling 4.5m onto the tarmac.

But he survived.

He was able to give the police information about the hijackers and their weapons before being taken to Singapore General Hospital.

On board, Mr Tan's condition was unknown, but Mr Ang assumed the worst.

“After Bernard was thrown out of the aircraft, which I didn’t know until later, I was getting the fear of, who will be next? Will I be the next person to get killed?” he said. “There’s fear, anger. I was asking myself, why is this happening to me?”

These feelings intensified as the violence against stewards continued. Mr Ang remembered Chief Steward Philip Cheong being slapped so hard that it left a mark. “I was preparing to die,” Mr Ang admitted. “I didn’t think that I would survive from the beginning.”

Wednesday, midnight: The ordeal drags on

Back in the cabin, Mr Ong noticed one hijacker was constantly drinking beer and offering cans to passengers, which they declined. Mr Ong was afraid the binge drinking would make him violent.

The same hijacker also started asking fair-skinned passengers for their nationalities, Mr Ong recalled. When one of the passengers said he was Lebanese, Mr Ong remembered the hijacker replying very loudly: “Your country is in a worse situation than my country.”

“I almost wanted to laugh,” Mr Ong said. “But I refrained from it.”

When a “big bloke” of a passenger told the hijacker that he was American, Mr Ong feared that a scuffle would break out. But nothing happened, and Mr Ong was relieved.

In the galley, the steward Mr Ang remembered chatting with the young hijacker who was with them. This hijacker seemed to be “very naive and innocent” and was just following instructions, Mr Ang said.

When the hijacker was asked why he wanted to go to Sydney, he replied that people of different races lived harmoniously there. When Mr Ang said this was the case in Singapore too, the hijacker said with a smile: “Yes, I want to go to Singapore.”

While things in the cabin were relatively calm, the situation in the cockpit escalated.

At midnight, hijackers splashed the cockpit and control panel with alcohol seized from the first-class cabin, and threatened to set the plane on fire. At about 2.30am, the hijackers lit up newspapers on the cockpit floor, and threatened to start a fire again.

In the command centre, Mr Lim said negotiators continued to assess how real the hijackers’ threats were, based on their experience with markers like the hijackers' tone of voice and the kind of language they used when communicating their demands.

“The most critical thing the executive group had to make an assessment on was: Are these guys serious? How urgent were their threats?” he said. “Because we must hope that we act in good time to secure the safety of all hostages.”

Negotiators eventually agreed to refuel the plane, and the hijackers put out the fire. At 2.40am, the plane was moved to a refuelling point on the outer tarmac of the airport. This was also a strategic move to put it at a spot where hostage rescues had previously been rehearsed.

The first load of fuel was delivered at about 3.30am. In the cover of darkness, Singapore Armed Forces (SAF) Special Operations Force commandos, clad in black and carrying short-burst machine guns, crept up to the plane.

“The SAF side had already put the commandos on standby,” Mr Lim said. “Mobilising the commandos to do the storming of the aircraft, that’s always the last resort, it is never the first resort.

“Obviously for this type incident, you always want to try to settle it peacefully, without the use of force if you could. But what's very important in the minds of all of us in the executive group, was that if there’s a need to use force, we will have to use the force.”

Wednesday, 3.30am: A near-death experience

At around the same time, the chief steward Mr Cheong became the second person to be thrown out of the plane. Then about an hour later, the Tommy Page T-shirt hijacker brought Mr Ang to the door with a knife pointed to his neck.

Mr Ang looked down and only saw pitch darkness. “I couldn't gauge how high I was,” he said. “At that moment, only two things crossed my mind: The first thing is either I died in the aircraft, or should I be thrown out, how am I going to break my fall.”

Just as Mr Ang prepared for the worst, the hijacker leader appeared and started arguing with his compatriot. Mr Ang was pulled back and asked to close the door. He called this his “closest encounter” with death.

The two remaining stewards were then asked to return to the main cabin to sit with the passengers. Mr Ang said this was the first time he got a proper look at the cabin, hours after being sequestered in the galley feeling “hopeless”.

Most of the passengers were resting, some asked him what was going to happen. “I just gave them a hand sign to say relax, everything will be okay,” he said. “I was too exhausted.”

Mr Ang remembered hearing the fuel trucks rumble up to the plane, and worrying about what this meant for the operation. “If the aircraft leaves Singapore, it might explode in mid-air,” he said.

Likewise, Mr Ong remembered hearing the fuel pumps turn on and feeling that chances of survival were “very low” if the plane left Singapore.

“But if we stay on in Singapore, I think we may have a chance to escape that hijack,” he added, remembering how the country had successfully tackled previous crises, like the Laju ferry hijacking at Pulau Bukom in 1974.

Wednesday, 5am: Sadness and calm before the storm

As the plane was being refuelled, Mr Ang recalled the hijacker leader assuring passengers that they would be released after this process was completed.

“So at that moment, there was a split second of happiness, telling myself, gosh, it's going to be over,” he said. “But the happiness didn't last that long.”

The hijackers insisted that the two stewards and the pilot stay on the plane to Sydney, and Mr Ang said the “lowest moment” was when it dawned upon him that “everybody is going home, except me”.

“A lot of emotions crossed my mind because I started to think about family, loved ones,” he said, his voice choking up as he spoke to CNA.

“I always say it’s not a fear of death. It was a fear of leaving my responsibilities behind. I thought of my younger sister, my cousin, my mum, even my dog. Who’s going to look after them?”

Mr Ang wrote two letters, one to his mother and another to his wife.

“I wrote a letter to my mum, and I told her that I've not been a good boy. And she's always been pulling me out of trouble and always there for me. I wanted to thank her ... and in my next life, we will still manage to be ...” he said, unable to complete his sentence.

Mr Ang passed the notes to a stewardess and asked her to hand them to his family if he did not make it. “She looked at me, didn't say a word and took the notes along with her,” he added.

Mr Ong, a Christian, remembered trying to recite scriptures from the Book of Psalms as he wondered if he would survive.

“I was praying for God to give me a second chance, a second chance that I may see, I may talk to, I may feel my family again,” he said.

“I've got two children, a boy and a girl. They were teenagers. So I thought, would that be the last time I would ever see them or hear from them?”

Nevertheless, Mr Ong felt his fear subside as he thought about the previous rescue operations that brought a happy ending.

“That calmed me down, and that did not bother me,” he added. “So all the time, I was looking forward. I was preparing for rescue and hoping that the rescue may come in time.”

Wednesday, 6.45am: Breaking point

Negotiations hit an impasse seven hours after they began.

As dawn fast approached, the hijackers informed negotiators that they were no longer interested in communicating. They threatened to kill one hostage every 10 minutes if their demands were not met. They issued a five-minute deadline and began a countdown.

In the command centre, Mr Lim said this presented a “very critical situation”.

“If we decide to storm the aircraft, the likelihood of the hijackers being killed was very high. If we don’t make a decision, the chances of an even more tragic outcome, which is the passengers and the crew being killed or whatever, would be far worse,” he said.

“And so, finding ourselves in that situation, we could not defer making a decision. You hope you are making the right assessment, but who is to say whether you did or not – there is no way to tell.”

This latest threat, coupled with the stewards being pushed off the plane, contributed to a collective decision to send the commandos in.

“Making that decision to storm was such a natural outcome from what we sensed of the situation,” Mr Lim said.

“At that point in time, everything was ready. The SAF was ready to move. People were all prepared for such a decision. But that doesn't mean we only had one choice. It simply means that when we hit that moment and recognise, okay, we have to decide, nobody said, why don't we wait a bit more?

“What more information could we be hoping to get if we delayed? Do we wait until they start killing the first hostage after 10 minutes before we conclude they are serious?”

After Mr Lim gave the green light, the room fell silent, waiting for news that the mission has been accomplished.

“Once you decide to storm, we assume the commandos will get the job done,” he added. “We have total confidence in our commandos, of course! Otherwise, they can't be our real last resort.”

Wednesday, 6.50am: The storming

The steward Mr Ang remembered dozing off, before waking up and sensing movement on the right side of the plane.

Six commando teams used special ladders to scale the plane and blew open its doors with explosive charges.

“Next moment, there was a stun grenade being thrown in and bam! Lots of guys in masks came on board and shouted, ‘Heads down, heads down!’” Mr Ang said.

“So what I did was I ducked under the seat, and the first thing I told myself was, thank God, finally they are here for us.”

The passenger Mr Ong also got down, feeling like he had “prepared for that event a long time ago”. “And when I heard the command, I said, my goodness, this (accent) is Singlish. And this must be the rescue that I was waiting for.”

As Mr Ong hit the floor, he heard a volley of muffled gunshots, likening it to the sound of toy guns. Two hijackers in the cockpit were swiftly shot. A third was killed in business class. The final hijacker was shot at close range.

Mr Lim said the storming operation took a few minutes, but official accounts said it was over in 30 seconds. Everybody was safe, including the two stewards who were pushed out of the plane.

“Of course, the commandos reported back immediately the job is done. You need to understand in the storming of an aircraft, we’re talking of a very fast operation, as it has to be,” Mr Lim said.

“You have to get into the aircraft. You have to surprise the hijackers. You have to make sure the passengers are all safe. You can't just be shooting any way that you want.”

Wednesday, 7am: The aftermath

Back at the command centre, there was applause, but the reaction among members of the executive committee was more muted.

“At that time, I think as a group we don't high-five,” Mr Lim said, laughing.

“I think for all of us it was in many ways a relief. Simply because our job was to bring the incident to an end, all the time focused on the safety of the hostages. The job is done. Everybody is relieved and everybody is happy about it.”

Everyone in the command centre had gone for hours without feeling tired or sleepy, Mr Lim said, simply because there had been a need to process new information that constantly came in. Mr Lim ended up sleeping for 12 hours when he got back.

Passengers were evacuated using the emergency slides and led in an orderly manner away from the plane, with instructions to look straight and keep their hands up.

WATCH: Days of Disaster: SQ Hijack

Mr Ong felt like a prisoner of war being marched around, but he did not mind as “it was good to smell the green, green grass again”.

“It was a second chance coming from almost a certain death,” he added. “And here I was given this chance to breathe the fresh air again and to watch the sun rising, for it was already almost 7am.”

Mr Ang was eventually identified as one of the stewards, before being interviewed by police officers. He requested to return to the plane to retrieve his uniform bag and staff pass.

Mr Ang said he saw the bloodied bodies of the hijackers in the plane, including the youngest of them he had chatted with.

“I felt sorry for him because it was a life wasted for something that was not worth at all,” he stated.

“What I think is not fair is that you shouldn't take other people's lives as a bargaining chip to get what you want. When your life is being decided by someone else, I think that is the scariest part, because you just don't know whether you’ll be next.”

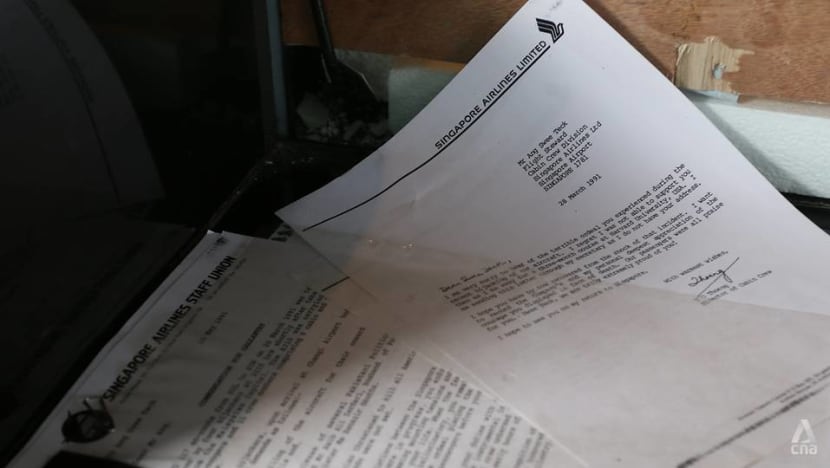

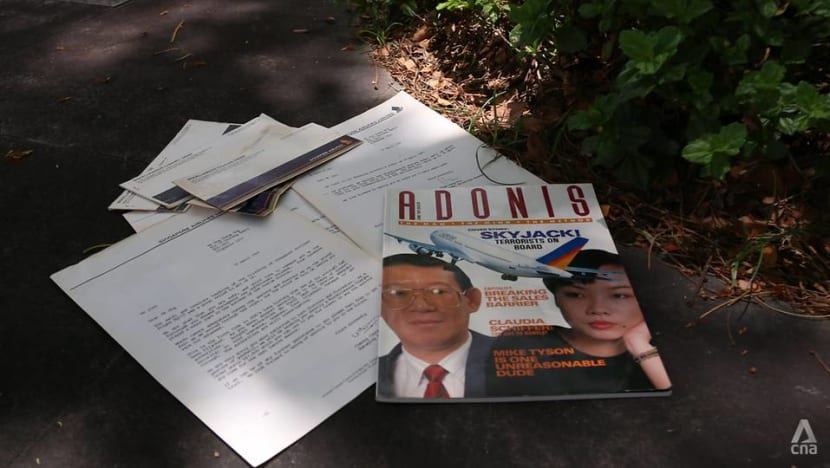

The weeks and months ahead

Mr Ang spent the next few days indulging friends and reporters eager to hear a first-hand account of what had happened. But then at night, these recollections gave him nightmares.

“I will remember the hijacker leader, I will remember the Tommy Page guy punching me, I will remember the knife at my neck,” he said. “But I think 30 years on, I’m coping quite well.”

To get away from further requests to speak about the incident, Mr Ang, who was on indefinite leave, requested to fly again just a week later. He ended up flying with Singapore Airlines for seven years.

“I wasn’t afraid of going back flying; I think I enjoyed flying,” added Mr Ang, now 53 and working as an interior designer. “I think it’s even scarier to stay at home.”

For Mr Ong, now 73 and retired, the experience of retelling the story to others was more therapeutic.

“I never dreamt about this incident these past 30 years,” he said, noting that he continued to fly for business or pleasure. “I think I've emptied almost everything off my chest. Maybe I was able to let go of everything.”

A few months later, Mr Ong was asked to go to Kuala Lumpur for another bank meeting. He asked his secretary to book a flight for him, but she said the only available seats were on SQ117.

“You had a bad experience before on this flight number. Now, would you want me to book a seat on this flight?” he remembered his secretary asking. “I said, ‘Yes, why not?’ I don't think lightning strikes twice on the same spot.”

On that flight, Mr Ong again requested a stewardess for a glass of milk.

“I said, ‘SQ117 owes me a glass of fresh milk.’ She looked at me in an unbelieving nature. What was I talking about? Then I told her (about the incident) ... and your stewardess never delivered that glass,” he said.

“So now, I just want that glass. And she gave a sigh of relief and started laughing. So I got finally, the glass of milk that I claim SQ117 owed me.”